Using socially engaged art to teach environmental and social justice

Chessa Adsit-Morris

INTRODUCTION

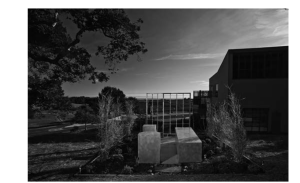

In November 2019, a participatory public sculpture and garden project was initiated and installed in the grounds of the University of California, Santa Cruz (UCSC) campus. Perched on a high hillside overlooking Monterey Bay, the installation features a six-by-nine foot metal replica of a U.S. solitary confinement cell, framed on one side by fabricated prison bars. The metal structure is surrounded on three sides by a garden designed by Tim Young, an inmate who has been living on Death Row at San Quentin Prison for more than two decades. The roses, sugar cane and daffodils planted by community volunteers at the entrance embody the nostalgia of childhood; the Swiss chard, kale, brussels sprouts, Irish potatoes, and pumpkin planted in the inner garden row embody sustenance; and the dudleya, lemon balm, mugwort, bergamot, and stinging nettle planted in the spring of 2021 embody a longing for healing and restoration. Young communicates through letters to UCSC undergraduate students and community volunteers who grow, plant and tend the garden, sending updates and photographs back to the prison. Created by jackie sumell – an artist who has worked at the intersection of art, activism, education, and mindfulness practices for nearly two decades – the installation is part of the Solitary Garden project, a socially engaged (art) practice aimed at cultivating conversations and fostering alternative imaginaries to the contemporary incarceration system by asking: “Can you imagine a landscape without prisons?”

Within months of the installation opening, the world was hit by a global pandemic that has, over the course of the last two-and-a-half years, exposed and exacerbated social, economic, and environmental injustice across a range of public institutions. The letters written by Young in 2020 after the San Quentin Prison was put into pandemic lockdown began to reflect the changing conditions and increased inequity felt by some of the most socially marginalized populations: prison inmates who have already been largely failed by legal, political, economic, and educational institutions. Research is now just beginning to illuminate the detrimental impacts COVID-19 has had on student populations, including a mental health crisis spurred by social isolation and a loss of critical in-person support services due to school closures and disruptions. The impact of the COVID-19 crisis on historically oppressed and marginalized groups has quickly dismantled any pretense of social equity in the U.S., leading to renewed calls for institutional reform. As a socially engaged art project, the Solitary Garden not only cultivated conversations between students, faculty, and community members about complex social and environmental justice issues – from inequities in access to adequate medical services, social services, healthy food, natural spaces for exercise and solace, increased exposure to pollution and environmental toxins, lack of legal protections and increased incarceration rates – but also functioned as a pedagogical site of community building, activism, and experiential learning.

This chapter explores the potential for socially engaged art to inform a re-evaluation and reimagination of higher education pedagogy post-COVID-19. The chapter begins by tracing the history of socially engaged art – broadly defined as a “social practice” that is collective and collaborative, and engages directly with the public sphere – from its roots in conceptual art and feminist performance art of the 1960s and 1970s to its emergence as a recognized art form in the early 2000s, and its development into an interdisciplinary practice adopted by a number of public institutions. In its expanded form as an interdisciplinary field informed by critical theories and radical pedagogies, and engaged with various cultural practices, socially engaged art has been utilized by educators – particularly, as we will see, at UCSC – to explore contemporary issues including globalism, immigration, social justice, climate change, intersectional feminism, and police brutality. The aim of this chapter is to explore how socially engaged art, as an interdisciplinary practice, can inform the creation of alternative pedagogical pathways that work across and between disciplines to address social and environmental justice issues, opening space within the classroom for criticality: an embodied state of knowledge production that draws on personal experiences to critically inquire into and understand complex real-world issues.

SOCIALLY ENGAGED ART

In 1992 a temporary exhibition titled “Culture in Action” opened in Chicago. Curated by Mary Jane Jacob, it represented what several critics and art theory scholars identified as a new trend in contemporary art: collaborative, site-specific, socially engaged art. Instead of being installed in a museum or gallery, the eight projects that collectively comprised the exhibition were scattered across the city, many in underserved communities. Each project worked collaboratively with a local organization or community group to conceptualize

222 Teaching environmental justice

and create each piece of art. As part of the exhibition, the Chicago-based artist collective Haha (which included Richard House, Wendy Jacob, John Ploof, and UCSC Professor Laurie Palmer), initiated a three-year project called Flood that worked with a local volunteer group to create and maintain a hydroponic garden in a vacant storefront in Rogers Park, a diverse neighborhood located on the north side of Chicago. The project produced vegetables and therapeutic herbs free of soil-based bacteria or other contaminants for people in the neighborhood living with HIV/AIDS, who lacked access to healthy alternatives or services. The project hosted biweekly meals for the community, and workshops on nutrition and horticulture; and functioned as a meeting space for community gatherings and public events. The exhibition was intended to be an institutional critique of both contemporary art institutions and healthcare institutions through the creation of a community-based mutual aid network. It was a micropolitical project, aiming to shed light on the larger context of our social relationship to disease, metaphorically connecting the IV lines that feed the plants to those that dispense medication, to cultivate dialogue, engagement, and empathy.

Speaking broadly from a socio-cultural standpoint, socially engaged art (henceforth SEA) grew in part out of the counterculture, civil rights, and feminist movements of the 1960s and 1970s, which pushed for anti-individualism and participatory democracy. This period was also one of the most significant decades in 20th-century art, with the rise of minimalism and conceptual art, performance art, installation, mixed-media, and feminist art, fundamentally contradicting high art’s aesthetic principles and challenging traditional relationships between the art object, the artist, and the audience. Influenced as well by Guy Debord and the Situationist International’s radical social criticism and revolutionary praxis, and Carol Hanisch’s 1970 germinal essay “The Personal is Political” – both of which were devoted to the disruption and reimagination of systems that govern everyday life – new forms of social art emerged, aimed at blurring life and art, and the private and political. These approaches to social art were based on models of institutional critique that, as Miwon Kwon describes, insisted on engaging “the social matrix of the class, race, gender, and sexuality of the viewing subject,” shifting the focus of art from representation to direct action. These new forms of social art were centered on process and site-specificity, positioning the viewer in the role of active participant. For example, Allan Kaprow’s “happenings” were structured performative events rooted in moments of everyday life; and fellow Fluxus artist Joseph Beuys’s conception of “social sculpture” as an expanded field of art where everyone is considered an artist was based on the belief that everyday actions imbued with creativity could reshape society.

By the early 1990s, SEA was more or less formalized (particularly in the U.S.) through exhibitions working at the intersection of conceptual art, public art, and activism – indeed “Culture in Action” and “Sonsbeek 93” (curated by Valerie Smith) were two of the first collective exhibitions considered truly socially engaged. SEA encompassed collective and collaborative art practices that occurred outside traditional art spaces; engaged with diverse audiences and communities (usually marginalized); and addressed a variety of contemporary social and environmental justice issues, including homelessness, pollution, racism, etc. As a result, SEA was by nature interdisciplinary, moving beyond the norms of artistic production by utilizing alternative media, and engaging diverse stakeholders including artists, activists, social workers, community organizers, urban designers, and ecologists. By the early 2000s, SEA was recognized as a global phenomenon by several art theorists and scholars, including Miwon Kwon, Grant Kester, Claire Bishop, and Tom Finkelpearl, to name a few. Funding organizations and academic institutions began supporting SEA work at international biennials and within various institutional settings, with a number of academic fields adopting SEA practices including new media, performance, education, legal studies, environmental science, architecture, and urban planning. As Michael Birchall noted: “This new field of activity [presented] an opportunity to produce work that provides a complex negotiation between the artist, the community, and the institution.”

Operating across various “social turns,” wherein social relationships and networks became the main focus of artistic interventions, SEA required new forms of critique and evaluation focused on process and impact as opposed to individual artistic genius or aesthetic qualities. As Irit Rogoff describes, the role of art (and the artist) shifted from representation and reproduction toward investigation, intervention, and reframing. SEA created opportunities for artists, curators, and their collaborators to address power inequalities within social structures, systems, and institutions; shifting from practices of institutional critique to the reconfiguration of institutional infrastructures through the creation of new systems, alternative networks, and collaborative practices that prioritized subjugated knowledges. Although critical debates emerged around the categorization and evaluation of SEA’s overlapping forms of social art practice – particularly around the level of aesthetic and formal sophistication, the emphasis on concrete social interventions and engagement with non-artistic audiences, and the level of institutional critique, aspects that vary significantly within each practice – SEA has informed the development of methodological practices within academic institutions that emphasize critical, participatory, and radical pedagogies, and community-based research.

SEA, EDUCATION AND CRITICALITY

A little over two decades before the Flood project occupied a storefront in Chicago, Allan Kaprow took over a storefront in Berkeley, California, and created Project Other Ways with progressive educator Herbert Kohl. The project was an experimental education initiative undertaken in collaboration with the Berkeley Unified Schools District, through which they engaged over 250 public school students and educators in a variety of workshops and semester-long explorations. When Kohl met Kaprow, he was teaching public school in New York at a predominantly Black and Latinx elementary school, and was discouraged by the U.S. education system and its ingrained institutionalized racism. As Catherine Spencer describes: “Kohl’s attempt to counter inadequate education and structural inequities began with rethinking the interactions between teacher and student.” Together they established an alternative model of learning for so-called “at-risk” youth based on collaboration and playful interactions with environments outside the classroom, emphasizing creativity, chance encounters, and democratic processes. That same year, Kaprow presented his educational ideas at UCSC as part of a one-year arts education research project initiated by Gurdon Woods, Chair of the newly founded UCSC Art Department, who was working in collaboration with Robert Watts, a founding member of Fluxus. Through the project, Woods and Watts created experimental arts workshops and brought in avant-garde artists such as Kaprow, John Cage, George Segal, and Merce Cunningham to participate and contribute to a publication on experimental education that included essays, curricula, project ideas, and excerpts of student experiences.

Kaprow’s collaboration with Kohl on participatory art and progressive education resonates with many other socially engaged artists – including Beuys, whose concept of social sculpture was informed by both progressive and radical pedagogies, and who established the Free International University in Düsseldorf, which aimed to foster interdisciplinary teaching, learning and research between the arts and sciences. Although education has always been a component of many social art practices to varying degrees, it wasn’t until the mid-1990s that an “educational turn” was formally recognized within artistic and curatorial practices. The term gained momentum and prominence after a 2008 publication in eflux by Irit Rogoff, noting how educational methods, processes, and programs had become ever more pervasive in contemporary art practices and their attendant critical frameworks. This marked a shift toward more pronounced engagements with formal and informal education sites and practices, and a convergence with broader critiques of neoliberal institutions. Many of these projects emerged in response to educational reform measures, critiquing not only what Paulo Freire called the “banking” model of education, but also the neoliberalization of institutions as increasingly instrumentalized and commercialized entities that promote and prioritize an ideology of competition and the proliferation of “free” markets. This transformation went hand in hand with the systematic defunding of the arts and humanities, promoting instead innovative market-driven advances in STEM (science, technology, engineering, and mathematics) fields.

Although the “educational turn” seldom found traction inside formal academic institutions, taking shape mainly in global museums and biennales, traces of SEA methods and practices can be seen in disciplinary micro-practices, including the emergence of transdisciplinary, participatory, and community-based research, and alternative pedagogical practices including project-based and service-learning opportunities within environmental, place-based and art education programs. Many of the micro-practices that make up this expanded field of SEA practices draw on a critical praxis based on the reciprocal nature of theoretical reflection and political action that is central to critical theory. Many of these practices are also informed and shaped by radical feminist interpretations of embodiment and criticality. Most notably for SEA, Rogoff put forth a conception of embodied criticality that was based on the “performative nature of culture” (no doubt drawing on Judith Butler), in which criticality moves beyond criticism and critique – which are all too often negative, dismissive and othering instead of practiced as a deconstructive process – and becomes a situated form of embodied engagement with practices of knowledge production and their institutional conditions.

CONCLUSION: RADICAL PEDAGOGICAL POTENTIALITIES

At a broader level, SEA forges direct intersections with social and environmental issues, fostering community coalition building in the pursuit of environmental recovery, community resilience, and social and environmental justice; and demanding more stakeholder involvement in institutional decision-making, representation of minorities, and policy changes. At an individual level, SEA provides opportunities for educators to “smuggle” radical pedagogical practices into their classrooms; disrupt normative and habitual forms of thought; recognize the value of students’ experiential knowledge and agency; and cultivate equitable classroom communities. As an expanded field of relational practices, SEA not only aims to make learning available and accessible to everyone – whether you are an inmate at San Quentin, an “at-risk” elementary student, a local community member, or an undergraduate student – but also attempts to makes possible the creation of imaginaries that allow us to envision a future wherein education contributes to the establishment of a just and equitable society. It provides democratic micropolitical spaces for students to explore real-world issues through personal embodied experiences and connections to affected communities from participation in community service and community science projects with local organizations, to mixed media oral history projects, to performative urban interventionist projects, to field trips to sites of interest.

Yet, as a contemporary model of SEA, the Solitary Garden goes beyond traditional SEA practices by explicitly grappling with connections between anti-racist social justice and political ecology, fostering a double consciousness that refuses to treat environmental matters of concern and sociopolitical injustice as separate issues. It exemplifies what T.J. Demos terms “ecology as intersectionality,” insisting on the inseparability of various systems of overlapping oppression (race, class, gender, sexuality, and ability) within the historical and contemporary contexts of environmental degradation due to extraction, pollution, and climate change. Its aim is dedicated to abolition and the end of the prison industrial complex as we know it, such that its radical educational pedagogy (and potential) is about equipping students, faculty, and community members with the social, emotional, and intellectual capabilities needed for a post-carceral society. It too functions as a micropolitical site – a space to learn and utilize the tools, practices, and imaginaries needed not only to address issues of equity in our classrooms but to imagine and strive for a just future.

Figure 14.1 UCSC The Solitary Garden

Figure 14.2 You can annotate this cartoon at https://bit.ly/ TeachingEnv-Humor